|

Kotlas - Waterville Area Sister City Connection P.O. Box 1747 Waterville, ME 04903-1747 Write to Us |

|

![[Show table of contents & options]](../../questionsign.gif)

|

Kotlas - Waterville Area Sister City Connection P.O. Box 1747 Waterville, ME 04903-1747 Write to Us |

|

|

Home > Impressions > Summer 1999 |

![[Show table of contents & options]](../../questionsign.gif) |

If you are viewing this newsletter without the table of contents, click the question mark sign anywhere that it appears to display the table of contents and other options. |

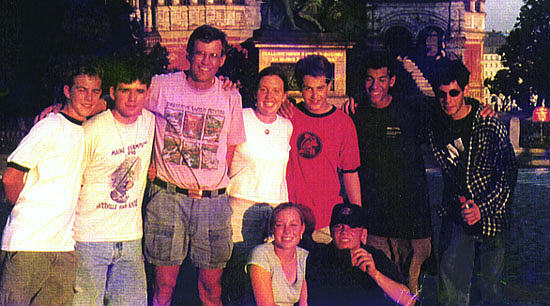

Standing from left to right, Brad Marden, Kevin Paul, Mike Waters, Melissa Clark, Burt Helm, Matt Reid, Andrew Beane, and (kneeling) Ali George and Mike Veilleux in Red Square in Moscow. The picture was taken by a passing Muscovite. |

Eight area teens recently had the time of their lives during a visit to Kotlas. Everywhere they went, they were treated like royalty. The travelers, students at high schools in Waterville, Fairfield, and Oakland, were members of a special class that had been meeting every few weeks for an entire school day to study the Kennebec River and its tributaries.

Their trip had been scheduled for April, but was postponed due to Russian displeasure over NATO's bombing in Kosovo and, ironically, the threat of severe springtime flooding on Kotlas's river, the Northern Dvina. The trip reciprocated for a February visit to Waterville by twelve Kotlas teens studying their river and marked the end of our yearlong Rivers Project.

The travelers were Brad Martin, Ali George, and Mike Veilleux of Messalonskee High School; Matt Reid, Burt Helm, and Kevin Paul of Waterville High School; and Melissa Clark and Andrew Beane of Lawrence High School. They were accompanied by Rivers Project instructor Mike Waters, a science teacher at Messalonskee, and Kotlas Connection Co-Chairman Phil Gonyar. Three other students, Cheri Young and Jessica Deane of Winslow High School and Crystal Dostie of Messalonskee, were also in the Rivers Project class, but could not go on the trip.

The group left Waterville on June 28. They had planned to spend five days in our sister city, but could only stay for four, as a delay in their flight from New York caused them to miss a connecting flight in Helsinki and, in turn, their train from Moscow to Kotlas. The missed connections did give them some extra time in Moscow, however. They toured the Kremlin, took a boat trip on the Moscow River and strolled and shopped on the Arbat, a historic street of shops that is now a pedestrian mall with street vendors and entertainers.

![[Show table of contents & options]](../../questionsign.gif)

After a daylong train trip, the group finally arrived in Kotlas on the evening of July 1. The next day, they took a bus to Veliky Ustyug, an historic town 40 miles upriver (south) from Kotlas at the confluence of the two rivers that form the Northern Dvina. On the way, the stopped at a village museum dedicated to the memory of a local naval hero. (See Phil Gonyar's essay below.) In Veliky Ustyug itself, they visited a monastery (which was normally closed for renovation but opened just for them) that had, they were told, "the third most beautiful icon wall in Europe." The following day, the students and their host families, around a hundred people in all, had a cruise on the Northern Dvina and the Vychegda (which flows into the Northern Dvina at Kotlas) on a large, double-decked passenger boat. They stopped twice, to play soccer and swim in the murky water, and then enjoyed an onboard feast, with contrasting music from an folk trio and a rock group.

The students' third day in Kotlas was July 4, and everywhere they went, they were showered with flowers in honor of America's independence. That morning, they took a bus to Ilyinsk-Podoma, a town 45 miles east southeast of Kotlas, where they saw displays of quilting, weaving, needlework, and birch bark crafts at a school for the folk arts. They then visited a local museum with eclectic collections of folk art, animal bones, and coins, and were entertained by a group of ladies in traditional costumes who sang, danced, and then taught them folk dances. After a multi-course midday meal, they rode the bus into the hills near the town, an area that the natives call "little Switzerland." There they met a "youngish" man who, several times a year, leads groups of volunteers to St. Petersburg to excavate the battlefields, searching for soldiers and civilians who had been hastily buried during the Siege of Leningrad in World War II. The group returns those bodies that can be identified to their families and re-inters the rest. Their motto: "The war will not be over until all the dead have been properly buried."

Phil Gonyar presents a letter of greeting from Waterville Mayor Nelson Madore to the deputy mayor of Kotlas. The letter was addressed to the mayor of Kotlas, who was out of town. |

On their last day in Kotlas, the group met the city's deputy mayor and laid flowers at a Kotlas war memorial. They then took a bus to Koryazhma, 20 miles up the Vychegda from Kotlas, where they visited a natural history museum and a children's summer camp, formerly state-run but now privately operated. That afternoon, they returned to Kotlas and attended a public reception in their honor, before boarding the train that took them back to Moscow. The travelers spent one more day in the Russian capital, during which they visited Lenin's tomb and the Moscow circus, before returning to the U.S. on July 8.

All the students found their trip enjoyable and educational. They were overwhelmed by the generosity of their hosts. In the words of Brad Marden, "All the families of Kotlas did all that was within their power to make us feel at home while visiting them. Although in reality I was thousands of miles from where I was born, I truly feel like I now have a second home in Kotlas. The amazing display of generosity was a strong testament towards the attitude of goodwill and peace towards all people in the world. This trip really helped eliminate any stereotypes and cautions I had toward the Russian people."

See more pictures of the trip!

![[Show table of contents & options]](../../questionsign.gif) |

A Visit to Kotlas: Four Recollections |

Below are essays by both of the teachers and two of the students who went to Kotlas in July. The editor added the italicized comments.

Ali George (right) hugs her host sister Elena Tarakanova before boarding the train to leave Kotlas. Photo by Mike Waters. |

As I was relaxing in the summer sun the other day relentlessly pondering what the focus of my article would be, I drifted off to sleep. Although my snooze was brief when I woke up I felt rather disoriented. Oddly enough the first word to pop in my mind was spasibo, Russian for "thank-you." This experience was strange to me and I'm sure that most people understand to feeling of being jolted awake as though they had suddenly fallen into their beds. So this article is going to attempt to explain precisely what happened to me on that hot summer day.

My first theory is that I was mysteriously transported from my lawn chair to a small Russian car packed with two very kind adults calling themselves my Mom and Dad and two teenagers who claimed to be my brother and sister. I recall being ecstatically happy and feeling right at home even though I couldn't even speak their language. We ate a lot of strange foods, steamed in a banya [like a sauna], gossiped until the early morning hours, tended a garden at the dacha [a summer cottage in the country], and played badminton in the streets. Nah, that couldn't possible have happened! I'm just a country girl living in Sidney, Maine. There's no way that I could be lucky enough to experience first hand a cultural exchange of that magnitude.

Having ruled out my first theory due to its improbability, my second theory is a bit more grounded. While I was napping my friends Mike Veilleux and Brad Marden slipped me some sleeping pills and transported me to a train station in Moscow, Russia where we met up with Melissa, Andy, Matt, Kev-bo and Burt to travel together. Having dropped our luggage at the station we spent the day gallivanting through the streets, seeing some of the most amazing churches, tombs, and structures in the world. Then we locked ourselves in a compartment on the train, played "Mafia" for hours — Burt is such a liar — debated the death penalty — You're wrong, but sly, Kev-bo — sang "Blue Jeans Baby" — Matt's a great singer — gambled — We were caught! — and Melissa and I even produced our own Herbal Essences commercial in the bathroom! Wait! That's crazy — no way could Brad and Mike sneak into my back yard without waking me up!

(In a subsequent e-mail message to the editor, Ali explained some of the references in the preceding paragraph: "'Mafia' is a game where two people . . . [are] chosen by secret lottery . . . and then the group debates about who are the Mafia members, and everyone votes to kill people off, and eventually either Mafia wins or the good people do. 'Blue Jeans Baby' is a cool Russian song that Matt fell in love with and sang for ever! 'Gambling' was when all of [us] . . . sat down to a game of cards and used any spare foreign or American change we could . . . for wagering — but then these two guards came by who didn't speak any English and made a big fuss about it and how it was illegal and unsafe. It was a good thing that Mr. Waters was around to interpret.")

My third and final theory is a bit out there, so please try and stay with me. Maybe my guardian angel swooped out of the sky and flew me to Russia. She brought me to Veliky Ustyug to tour a few cathedrals and museums and shop for Russian blackened silver. Then we flew over the River Dvina singing songs and playing on the beaches. Ilyinsk-Podoma was our next stop, where we flew into a museum for dancing, games, and lunch, before we met the mayor and visited a computer school. We also made a quick stop in Koryazhma to enjoy a concert by Russian musicians, went to a former pioneer camp, did a little shopping and got down at a disco party.

Honestly, I'm not sure that even my third theory would hold up against questioning, because last I knew, my guardian angel — although it sounds strange — doesn't enjoy long flights, and trust me, from my house to Kotlas is a lo-o-ong journey. Although my article was not successful in correctly identifying precisely what happened to me on that sunny day in my backyard, it has brought me many fond memories. I hope it isn't too corny to add that I have come to the realization that the reason the word spasibo was on my lips is that I am so grateful for these memories. I want to thank everyone who contributed to the Kotlas Connection's effort to send the gifted and talented science program to Russia. I know that I am speaking for all of us when I say that these memories will live forever and that the friendships that have formed across our continents will warm our hearts for many years to come.

by Ali George

Ali George is the daughter of John & Gail George of Sidney. A June graduate of Messalonskee High School, she is now a freshman at Bowdoin College in Brunswick. She plans to do a double major in math and physics.

![[Show table of contents & options]](../../questionsign.gif) |

A Visit to a Museum for a Young Hero |

Our arrival in Kotlas on the evening of July 1 brought an enthusiastic greeting. Many had come down to the train station to meet us, as is the custom of the Kotlas folks. Bouquets of flowers, hugs, and hearty backslapping were followed by dispersal to the various homes where we were staying. Getting reacquainted (and eating) was the order of the evening. Next morning early we were to go on an excursion to Veliky Ustyug, so some rest was in order.

Brad Marden (left) and Mike Veilleux at the Preminin museum. Photo by Mike Waters. |

En route to Ustyug the next morning, we stopped at a school in Skornyakovo. In this village was a monument and a museum to the Soviet naval hero Sergei Anatolyevich Preminin. Seaman Preminin was a crewmember on the Russian submarine K-219. During the Cold War [in October 1986], this nuclear submarine was cruising off the American coast when it collided with an American submarine. [To this day, the U.S. Navy denies that any such collision took place.] The Russian submarine caught fire, and a nuclear disaster seemed imminent. Preminin volunteered to shut the reactor down manually, since the automatic systems had failed. He managed to do so but was unable to leave the compartment; the door was jammed. He died of asphyxiation. Peter Huchthausen, writing about the incident in his book Hostile Waters, says, "Sergei Preminin, son of a simple flax worker, had saved an atomic submarine and her crew." And, perhaps, thousands of civilians nearby.

The incident did not become public for several years, but Peminin's heroism is now public knowledge. At least one of our students had seen the movie made about the incident and so had foreknowledge of the affair. [A made-for-TV movie based on the abovementioned book first aired in July 1997 on HBO. The movie is now out on video.] The local students who staff the museum and the teacher who organized it explained the items displayed. [The museum is housed in the school the Preminin had attended as a youth.] Preminin's parents, still living nearby, came to the museum to meet and greet us. They showed the intense pride that they have in their son and their appreciation for the positive responses received from Americans who have supported the museum. The emotion surrounding our visit was intense. It is just one example of why the trip will be unforgettable.

by Phil Gonyar

![[Show table of contents & options]](../../questionsign.gif) |

Impressions of Russia |

On the flight back to New York from Helsinki, I had to have a window seat. I love geography and wanted to put images to maps. Now as I work my way back into my normal life, I see that the window seat provided a more valuable service. The northern European countryside looks quite similar to that of Maine. Our friends that we stayed with and the new people that we met made the eight Waterville area students in the Rivers Project, Phil Gonyar, and me feel so welcome. It was almost as if we had not left Maine. Seeing Scandinavia roll into the Atlantic, interrupted only by Iceland and Greenland, helped me remember that we had been very far from home.

Of course there were some major differences. I recognized very few of the birds. Due to the "White Nights," I had to put a T-shirt over my eyes at night to get to sleep; stars were never visible in the sky; and a camera could be used outside at night without a flash. [From mid-June to early July, days in Kotlas are more than nineteen hours long, punctuated only by several hours of twilight. During this time, it never really gets dark.] I ate dinner at breakfast and repeated this ritual three times a day. I could not understand the conversations around me. A twenty mile trip in Russia is a carefully planned undertaking. [Many Russian families do not own cars.] A kitchen garden is both a necessity and a work of art.

The symmetry of our trip mimicked the harmony of a Russian meal. We traveled by air for one day, spent a day in Moscow, spent a day on the train to Kotlas and four days in Kotlas, only to repeat the process in reverse. Our self-confidence in these surroundings grew as the days progressed. It was as if every stage was planned to integrate us effortlessly into our new setting. The Russian meal progresses in a similar fashion, the first course leading to the second and back to the first with tea added. The end effect is digestive contentment and spiritual energy to balance the lack of sleep. I found myself thinking that I needed to change my eating habits when I got home. I know that I need to revamp my gardening knowledge. The only way that our trip could have been better was for it to have been longer. As time progressed, I wanted to ask more questions, sit in on conversations around more dinner tables, learn more Russian to understand better the subtleties of these exchanges, see more countryside, be taken to more of their special places.

You would have felt the joy of the experience if you had seen the students walk across Red Square the night before we left. At the time, several of them said that this was either the highlight of their lives or close to it. These statements were reflected in the smiles radiating from my photographs of this evening. If you look closely, you can see the same sentiments in the photographs of our tearful good-byes at the Kotlas train station the previous morning. Several of us promised that we would be back. As for myself, I want to work on my Russian and come back more than once. I even want to see Kotlas in the winter, so that I don't need a futbolka ("T-shirt") over my glaza ("eyes") to fool my brain into otdykhat ("resting"), and so that I can see the season of which my host family spoke so tenderly. I just want to see everybody again.

by Mike Waters

![[Show table of contents & options]](../../questionsign.gif) |

Memories of Kotlas and of My Host Family |

As our train pulled into Kotlas's main train station, I was somewhat surprised by the number of people waiting for us. More than fifty people stood on the platform, some with flowers, others with video cameras. There were some familiar faces in the crowd, the people whom we'd hosted in Maine and had now traveled thousands of miles to see. The majority of the people, though, were unknown to us. Many of the unknown faces belonged to the parents, siblings, and relatives of our hosts, but there were also people who had been drawn to the train station just to see a group of Americans, a fairly uncommon sight in that part of the world.

I stumbled off the train with my heavy suitcase and was immediately greeted by Andrei [Vlasov] and his family. They quickly relieved me of my suitcase and backpack, insisting that they carry it to the car. As we walked to the parking lot, I glanced up at the pink stucco facade of the train station, probably the most handsome and well-preserved building in Kotlas. The hammer-and-sickle relief on the building had been painted over, but its outline was still visible. We came to the square at the opposite side of the station. I was surprised to see a statue of Lenin at the far end of the square. A motley assortment of small automobiles was parked near the statue; we got into a red car and headed off toward [the apartment that would be] my home for the next four days.

The drive took about 5 minutes. I'd known what to expect in Kotlas, but was still taken aback by the disrepair of the city. The roads were in a terrible state. The huge potholes dotting the busier streets made for driving full of sudden stops and swerves. The Russians didn't let the poor roads hinder them, though; driving was fast and passing on small, two-lane roads was very common. All of the public spaces were overgrown with weeds and uncut grass. We passed row after row of nearly identical apartment blocks on the way to my family's flat. On the outside, these buildings looked worse than the roads. Large areas of the buildings' exteriors had no paint, showing the ugly brick-and-mortar construction. Although no more than fifty years old, many of these buildings looked as if they wouldn't last another half-century. The entire city bore a very strong resemblance to the blocks of government housing projects that I'd seen in the south side of Chicago or the Bronx.

We arrived at my family's apartment building and entered through a ground-floor doorway. We walked up three flights of concrete stairs in a musty, dimly lit corridor. We finally arrived at the flat's door; it was covered in leather and had the number 54 inscribed on it. At this point, I really had no idea what to expect to find in the apartment itself. Andrei opened the door and I stepped into a relatively small and very cozy four room apartment. The rooms were well furnished and the family had many of the amenities that Americans do. If I had been shown this apartment and an apartment in Waterville, I would have had trouble distinguishing which was which. The disparity between the exterior and interior of the apartment was simply unbelievable.

I hardly had time to admire the place, though. I was constantly being asked if I wanted anything — whether I wanted to sit in the living room or the bedroom, if I needed to use the bathroom, where I wanted to put my backpack, if I wanted to eat a lot or a little. My response to the final question was "a little," so we sat at the living room/dining room table and my host mother served a "little" three-course meal. The meal, in fact, was far from little. The meal was more than I am accustomed to eating at a normal meal at home — and this was only a snack! We sat at the table for a long time, talking about everything. Finally, a little after midnight, we went to bed with the knowledge that we'd have to wake up in a little over five hours.

![[Show table of contents & options]](../../questionsign.gif)

I sat in my bed for a long while, though. The room in which I slept usually housed Andrei and his sister; they were sleeping on the living room floor for the next four days, though, leaving the entire room to me. The hospitality and generosity of my host family was hard to believe, yet very touching. It was not an anomaly; throughout Kotlas, members of our group were being pampered and spoiled. This treatment would last throughout our stay, too. After a few days, I decided to do some laundry, so I asked Andrei if I could use the bathtub. He immediately protested, saying that his mother could do it. I didn't want to impose more than I already had, though, so I maintained that I could do it myself. My host mother then arrived on the scene, insisting that she do the laundry for me and virtually taking the dirty clothes out of my hands. Afraid of causing a scene, I relented. A few hours later I found my clothes, washed, ironed, and folded, sitting on my suitcase.

The day before our departure, my host mother asked what I'd need on the train. I replied that all I needed was some bottled water, bread, and cheese. They knew that I preferred non-carbonated water, but they didn't know where to find any. Undaunted, my host mother set out that afternoon on foot on a quest for precious "water, no gas." She finally found it after searching for almost an hour. The next morning, on the way to the train, I found some chocolate, home-made pizza, oranges, and sausages in my food bag in addition to the bread and cheese that I had requested.

That last morning in Kotlas was cold, much colder than I had expected, and I was quite cold in my shorts and T-shirt. My host father offered me his jacket, and we went through the same old game of my declining, their insisting, and finally my accepting. In the whirlwind of events that morning, though, I unwittingly boarded the train with the jacket still on my shoulders. Only minutes before the train pulled away did I realize my mistake; I quickly lowered a window and handed the jacket back to Andrei. My host father must have noticed it, but he didn't say a word. It was as if he had been prepared to let me take the jacket home with me.

Throughout our stay in Kotlas, though, I reminded myself that these people had no need to give us anything. I just wanted to see how they lived when they weren't entertaining guests. There was always a car available to transport us around the city. I wonder if they do so much driving during the other days of the year. And at the dinner table, our hosts continually heaped more and more food on our plates. I tried to decline on numerous occasions, but my family rarely gave my protests any heed and simply gave me more food. I was also quite surprised to find a number of oranges waiting for me. I'd always been under the impression that citrus fruits were rare (and very expensive) in Kotlas. I wonder if they eat so much (and so well) during the other days of the year. For some reason I don't think so.

At the end of my stay, I was showered with gifts: books, a porcelain doll, and a number of ornate wooden boxes, among other things. And they didn't need to give us anything. I'm sure that our hosts were aware of the differences in economic class between our two groups. For the purpose of our trip, this inequity made no difference and, for the most part, it was ignored. I'm glad that no attention was paid to wealth or similar subjects. Still, the Russians must have known that we didn't need to be given all those gifts and all those extra things, that we could buy them for ourselves. Even simple things like bottled water — water that I alone would use — they insisted on paying for. Why? I believe it's in their nature. I hate to stereotype here, but if there is one overall impression that I drew from Russian people as a whole it is that they are kind, generous, and warm-hearted people. Russians will go to excessive lengths to make their guests comfortable and happy, and go far out of their way to pamper them.

Why then, I ask myself, did we endure a forty-five year cold war with these people? These people who are kind and generous and could not possibly wish us any harm — just as we would like to believe that Americans would never wish them any harm could not and should not have been our mortal enemies for an entire half-century. How could countless Americans over the course of several decades be influenced by fears of a "red scare" or a "missile gap" when Russians, just like Americans, simply wanted to raise their families well. There is no reason for there to be a conflict with these people. All the world needs to do is to open its eyes and realize that the whole premise is ludicrous. Kotlas has opened my eyes, and I am thankful for it.

by Matt Reid

Matt Reid is the son of Clifford Reid and Sheila McCarthy of Waterville. He is now a senior at Waterville High School.