|

Home > News > Archives > Natalia Kempers > Remarkable Natalia Alexeevna

The Remarkable Natalia Alexeevna:

A Russian Soul in America

By Gregor Smith

At first glance, the wooden structure resembles a typical New England church. As one gets closer, however, one notices the small, robin's egg blue onion dome and spire in place of steeple and the bilingual signs, in Russian and English, out front. It is the Alexander Nevsky Russian Orthodox Church in Richmond, Maine.

It was an unseasonably mild Sunday afternoon, the last day of October. Gamboling zephyrs wafted through the church's open windows. Inside, the priest, wearing a floor-length, black robe and standing with his back to the congregation, intoned blessings in English and Slavonic, the ancient language of Russian Orthodoxy, for "His servants who are asleep." At intervals, the priest paused and the choir, comprising two young women and a young man, offered its muted a capella responses. Periodically, the priest stopped reading and walked in front of the altar, waving a censer to disperse the sweet incense throughout the room.

Such was the farewell for Natalia Alexeevna von Ranchner Kempers, a founder of the Kotlas - Waterville Area Sister City Connection. This was her panikhida, a memorial service held on the fortieth day after death, when, according to Orthodox belief, the soul ascends to heaven.

Although she lived in America for nearly five decades, her soul always belonged to the land of her ancestors. It was her desire to reconnect with her roots that drove the development of a sister community relationship between Greater Waterville and Kotlas, a city of 80,000 in northwestern Russia.

She had been born in 1923 in Yugoslavia. Her parents were Russian refugees. They had met on an icebreaker chugging out of the Port of Archangel in the Winter of 1920, shortly before the city to the advancing Red Army during the Bolshevik Revolution. Her mother, Lydia Yestifeyeva, was a recently divorced nurse from St. Petersburg. She was a graduate of Smolny, the famous school in that city for young ladies. Her mother's father, Pavel Yestifeyev, was a pioneer aviator who had been awarded a medal by the tsar, but whom the Soviets had incarcerated and executed in the notorious prison on the Solovetsky Islands, a forbidding archipelago in the White Sea, north of the Arctic Circle.

Natalia's father, Alexei von Ranchner, whose ancestors had come from Bavaria, was lieutenant in the tsar's military. His ancestors had immigrated to Russia from Bavaria generations earlier; his great grandfather had been personal physician to the tsar.

Young Alexei ran out across the ice after the ship. As he approached, someone threw down a line so he could climb aboard. It was there that he beheld the pretty, young divorcée for the first time. The two young refugees married and settled in Yugoslavia, which was then known as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. On October 7, 1923, Lydia von Ranchner gave birth to twin daughters, Natalia and Marina.

The girls grew up in a community of Russian émigrés, attending a Russian school. Life was hard; there was little money.

Now fast forward ten or fifteen years. In 1944, war raged throughout Europe. The Red Army was advancing into Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia. Natalia, her mother, and her twin sister — her father had since died — fled to Czechoslovakia. There they found work in a candied fruit factory. In 1945, with the Red Army continuing its advance, the three women fled again, this time to Germany, now occupied by the western Allies. In picturesque, historic town of Regensburg, Natalia met an American soldier, Frank Michael Reilly, who would become her husband.

The following year, the newlyweds came to the United States, to Washington, D.C., where she would become a Russian language teacher for the federal government. She and Frank Reilly would raise their four children there.

In 1973, Natalia moved to Waterville with her second husband, John Kempers, a Russian professor at Colby. She was hired as a library assistant, working behind the circulation desk in the college's main library. There she became a tutor and surrogate grandmother to Colby students who were learning her native tongue.

It was there also that she became acquainted with Peter Garrett, a local hydrogeologist and Quaker, who taught at Colby during the late 1970's. It was Peter who, in 1982, conceived of pairing Greater Waterville with a similarly sized community in Russia. In the early 1980's, alarmed at politicians' rhetoric about the "Evil Empire" and fearful of nuclear war, many men and women of good will sought to form sister city relationships with Soviet towns, to make the idea of hurling bombs at each other truly unthinkable.

Peter was one of these. He visited the Colby library to consult an atlas and the Great Soviet Encyclopedia to find a suitable city. Having selected Kotlas, he enlisted Natalia's aid to make contact with that city of 80,000 on the Northern Dvina River, which flows into the White Sea 335 miles later at Archangel, whence Natalia's parents had fled six decades earlier.

Peter, Natalia, and other like minded citizens solicited endorsements of their plan from the town councils of Waterville, Winslow, Fairfield, and Oakland, and in June of 1984, they mailed a "Community Portrait," containing maps, photographs of "ordinary people doing everyday things", the council endorsements, products from local factories, portfolios from a couple of schools, and a "Resolution for Peace" signed by over a thousand local citizens off to that mysterious city in northwestern Russia. Then, they waited.

In February 1985 came the long-awaited response. The then-mayor of Kotlas wrote, thanking the sister city organizers for the gifts, but making it clear that he had no interest in forming a sister community relationship. The pairing project appeared to be dead.

It wasn't. On receiving that letter, Natalia dashed off a postcard to the mayor asking him to arrange for her to correspond with "an ordinary mortal" in Kotlas. "I am an American citizen by choice," she wrote, "but I grew up loving Russia, the old Russia, not the Communism. It's a broken heart, you know. So many people, Russian people, are buried all over the world."

One day, Slava Chernykh, an engineer at the Kotlas shipyard came to see the mayor. An avid stamp collector, he noticed the postcard with its intriguing stamp on the mayor's desk. In response, he sent a letter and the two new friends continued to exchange letters and stamps.

As the Cold War melted into a glorious spring, other connections sprouted between the two communities. In December 1986, the Kotlas branch of the Young Pioneers, the Soviet equivalent of the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, sent their own "community portrait" of paintings, crocheted doilies, woodcarvings, and other handicrafts made by children in Kotlas. By the fall of 1988, Waterville area school children were exchanging letters with pen pals in Kotlas, and articles about Waterville were appearing in the Kotlas newspaper. Finally, on a dreary, late winter day in April 1989, Natalia, Peter, and Peter's daughter Jessica became the first Americans to visit Kotlas since the Bolshevik Revolution.

The joyfulness of their reception contrasted with the dreariness of the weather. Everywhere the visitors went, they were welcomed with warmth, enthusiasm, and also curiosity, as most of the people they met had never met an American before. They visited a school, a kindergarten, the House of Pioneers, the city's main library, the newspaper, city hall, and a paper mill in a nearby town. At the city hall, they met the city's new mayor, who had been appointed just a few weeks earlier. He greeted the trio warmly, which boded well for the future of the sister-city exchange. Indeed, in June of the following year, that mayor came to Waterville and signed an accord, formally declaring the two towns sister cities.*

Natalia returned to Kotlas twice, in April 1991 and June 1993. Since then, she has hosted visitors from Kotlas and taught and translated the Russian language to and for members of the Kotlas Connection. In October 2001, the Kotlas Connection honored her as its volunteer of the year at the REM Community Awards Ceremony.

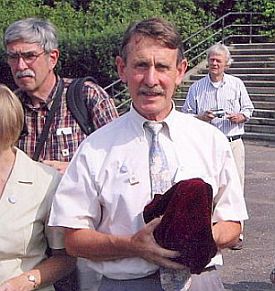

Peter Garrett holds a cloth-shrouded container of Natalia's ashes, which he is about to pour into the river in Kotlas. Behind him are Carl Daiker (left) and Herb Foster. Photo by Gregor Smith. |

On September 22, 2004, two weeks shy of her eighty-first birthday, Natalia passed away peacefully at the Lakewood Manor Nursing Home in Waterville. Her health had been failing for several months. She left behind her four children from her first marriage, three of her stepchildren, two grandsons, a niece, a nephew, and her twin sister, Marina Alexeevna Tate of New York City.

Part of her ashes were buried on September 24, 2004, in Pine Grove Cemetery in Waterville. It was her wish that the remaining portion by scattered over the Northern Dvina in Kotlas. That wish was granted the following August, when a delegation visiting from Waterville, along with member of the sister city committee in Kotlas, held a solemn ceremony at the Kotlas riverboat station.

Natalia was a quiet but determined woman. She spoke when she had something to say, but had the grace to remain silent when she had nothing to add. While we mourn her passing, we rejoice that she lived among us for so long. Our own lives and the lives of our twin communities, in Maine and in Russia, are enriched for our having known her. She truly was, as a Kotlas letter writer once greeted her at the top of his epistle, the "remarkable Natalia Alexeevna."

*For a more detailed history of the early days of the sister city pairing, see Discovering Kotlas: A Sister-City Retrospective.

<— Back • Top

|